Recent Reading

Narnia; JFK; baseball

The below are excerpts, sometimes elaborated, from my reading journal. I’m not careful with spoilers.

The Chronicles of Narnia

Having read so many children’s books in the the last few years, I’ve come more and more to admire Lewis’s Narnian prose. The only book we’ve read so far that feels as accomplished, if wholly different, is Mio, My Son, by Astrid Lindgren.

What might be even more amazing is how lightly sketched Narnia is on the page, and yet it exists fully painted in one’s mind. It becomes less of a fairy land as you work through the seven books, and is never really a fairy land in that it feels too medieval, too derivative of the courtly romance tales of Lewis’s scholarship. At the same time, there is no better place to ride on the back of a lion or to talk to a tree or to hunt a white stag that can grant wishes—in other words, fairy land.

Lewis’s greatest gift—and where he and Tolkien actually overlap, despite being foils in so many other ways—is to use a fictional world to detail all the things he loves best in this one. Good food, beautiful woods, wonderful walks, and more.

As for the books on an individual level, The Silver Chair is the most complete. It’s hard to top the wonder and emotion of The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe—the girls’ ride with Aslan through the fields to the Witch's castle is hard to beat for pure, childlike joy—but the narrative unity of The Silver Chair is almost perfect. By which I mean PUDDLEGLUM EXISTS. Give me all your dirge-dampened hymns for the loyalest marsh-wiggle that ever lived. Gallant Grump. Conscientious Crank. Saintly Sourpuss!

What Lewis does well in every book, though, is to scale the moments of courage largely at the level a child might understand—you must remember the most important rules; you must dare to be laughed at by your siblings; you must give up treats and comfort because the situation demands it.

There’s real physical danger, of course, but the children who go to Narnia are most worried about looking silly and sounding silly and about not getting enough sleep or getting wet in the wrong clothes. They’re cranky and they don't want to make the effort. They know they must obey Aslan's fourth sign, but they just promised they wouldn't untie the Knight! Can’t they sit down for a bit?

Even though his heroes battle and flee and thieve and more, the facet of courage which Lewis brings beneath his narrative microscope is almost always the moment of social nerve. Not just, “Can I swing my sword at this serpent though I might die?” But, “Will I be humble before my brother and sisters? Will I tell my classmate I was wrong? Will I split with my neighbors, who are all jeering what I actually believe?” It’s a simple view of life, maybe. Virtue isn’t always so clear-cut. Many times, it’s hard to distinguish between prudence and anxiety; that is, between what seems right on the balance of wisdom and insight, versus what I might prefer, being a jellyfish of a man.

But it’s like good old Puddleglum says, “That fellow will be the death of us once he's up, I shouldn’t wonder. But that doesn’t let us off following the sign.” Our discomfort is not meant to be our master, and is often the cause of much greater wrongdoing than might seem possible at first. Puddleglum says many other and even better words. Our family favorite is, “Respectowiggle.”

The Tears of Autumn, by Charles McCarry

Who killed JFK? Like everyone else living in 1963, that’s the question for Paul Christopher, Charles McCarry’s undercover CIA handler who speaks French and German like a native, and who finds himself supporting agents in Europe, the Congo, and (most importantly) Vietnam. A man who dislikes JFK and his posse of imitative New Men, Christopher weeps when he hears the president has been shot. He also knows, within a day or two, who sponsored the murder.

I mentioned McCarry’s first novel, The Miernik Dossier, recently. The Tears of Autumn is less successful, if only because I’m pretty sure most spy novels are less successful than The Miernik Dossier. McCarry, though, was a CIA undercover man himself, and was rediscovered in the mainstream for a bit in the early 2000s because of his novel The Better Angels, which features terrorists taking over planes as means of mass desctruction in the year 2000. It was published in 1979.

All of his books have that realpolitik feel. They’re romantic adventure stories squeezed through the mind of someone who knows that spying involves a lot of memos and enough information gaps in the name of security that any number of realities can and will co-exist regarding even world historical events.

As for JFK?

South Vietnamese president Ngô Đình Diệm was assassinated in a CIA-backed coup 21 days before Kennedy. Within a short time frame, Christopher finds all the intermediaries that suggest JFK’s assassination was a Vietnamese revenge plot—some a little less practical than you might expect from McCarry. I don’t know how accurate McCarry’s interpretation of Vietnamese cultures and family structures is, but he takes pains to give the nation circa 1963 and its people a specificity and alienness, from the American perspective, that doesn’t simply reduce them to the exotic or simplistic. There’s still a lot of damning caricatures, of course, which was bad then and is bad now.1 His point, though, is to emphasize that a small country’s president being assassinated is as dirty a deed as a large country’s.

McCarry is a convincing conspiracist. The novel takes place before Bobby Kennedy’s later assassassination, and our main man, Christopher, points out that the Vietnamese won’t have their revenge until Diệm’s brother, also killed in 1963, is accounted for as well.

The Natural, by Bernard Malamud

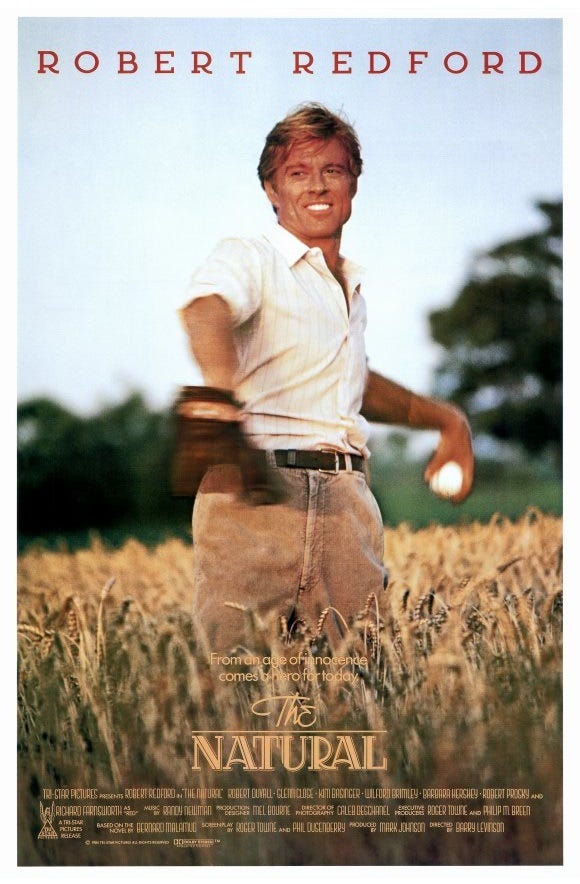

This novel was as surprising, in many ways, as its film adaptation when I first saw the latter in high school. Whereas the film looked hokey on the outside—the cover features a golden Robert Redford tossing a ball like he’s about to star in an afternoon special titled “Weekend Dad”—Malamud’s text felt dated from the outside. Not sure why. Perhaps simply because it’s a book about baseball during baseball’s dominance within American culture. I was wrong, and maybe a little right, on both counts, but more surprised than prophetic.

Malamud is the model for the older author in Philip Roth’s The Ghost Writer, and that character’s famous, “I turn sentences around,” description of writing feels very accurate to this novel. Malamud is a stylist above everything. He flirts with the same problem C.S. Lewis ascribed to Golding and his novel about Salisbury Cathedral: Malamud almost writes too well. The flare sometimes obscures everything except for itself. What flare, though!

Malamud understands the spiritual nature of sports, the way fans and society and the players themselves invest a holy, damning, unreasonable level of personal stakes into the results of adults playing schoolyard games. The dream sequences, the action sequences that read like dreams: the superstitions of ball players are not incidental to sports, but the very heart of them. All the melodrama of this novel, and all the pyrotechnics of Roy Hobbs's off-field life, are able to ape novelistically the very highs and lows of being a sports fan. The incandescent, prophetic feeling of a team of destiny tearing off win after win. The cruel, unraveling effect of that same invincible unit collapsing, getting injured, selling out.

Malamud has transformed the drama of the field into sentences; he really has. Even the gut punch at the end scans: here's a writer who has loved a team and seen them lose at the very moment he finally believed they might win.

The movie ends on a much different note, predictably. My thoughts haven’t congealed around the last page of the novel yet, but when I finished it I stared at the wall for two or three minutes in a kind of shock. Maybe this is the thickest stew of self-stirring prose an American has ever cooked up? Maybe it’s the lucid dreaming of America’s conscious mythic-making made manifest? Not sure! Either way, it’s worth reading.

I love you all.

Arguably, what makes some of his Vietnamese characters less egregious is that his Americans and Australians and Germans are also endlessly caricatured. He plays with these simple depictions in intelligent ways, but he enjoys broad characterization, at least as a setup, more or less universally.